SÃO MIGUEL

OF PAINTING AND THAT WICH IS SACRED - THE TENDER QUADRILLE

1. Carlos Vergara is a painter. Carlos Vergara also is a traveler. He travels to paint, using the dazzling moment of seeing something for the first time as the driving force of his visual poetic. Therein derives his intensity and multiplicity. Bedazzlement requires intensity so that the shock, typical of the admiring fright of something new and the Other, is not excessive when transposed into a work of art. This intensity is achieved in the studio, in the slow effort of the gesture, the brushstroke, the eye-hand-thought. Exercising the occupation of contemporary painter is a kind of technical conquering, of knowing how to do something, of dexterity. Virtuosity is exceeded in the search of the poetic. That is the only way bedazzlement can still manifest itself. For its part, multiplicity comes from the fact that Vergara transforms each trip, each landscape, each topography, every detail into a world filled with affections, into a new artistic materiality. Whether in the photography, the monotypes, the canvases, the world perceived is appropriated, transported, reworked and reinvented. His painting seems to be always changing, but only in this way does it become available to what is proper for each situation. One important question for the traveling artist is this availability for the other, the care taken with the differences. As Ovid wrote of the 1st Century of the Christian Era, “everything changes, nothing disappears.” Change to reveal and remain. Metamorphosis is an unstable form because it is crossed by the mutations of time and feeling. What had been seen in the locale the artist passed through is revisited as if for the first time, on the surface of the canvas or the palpitations of the 3D photographs. It is fundamental not to confuse the motives of the trip with some factor illustrative of the artwork. The pretext does not determine the text, nor what is seen with what is visible. In truth, the work retakes the trip. This is not to reproduce what was there but rather to make a pictoric happening of bedazzlement. Down deep, the trip is a metaphor for the poetic — the act of searching.

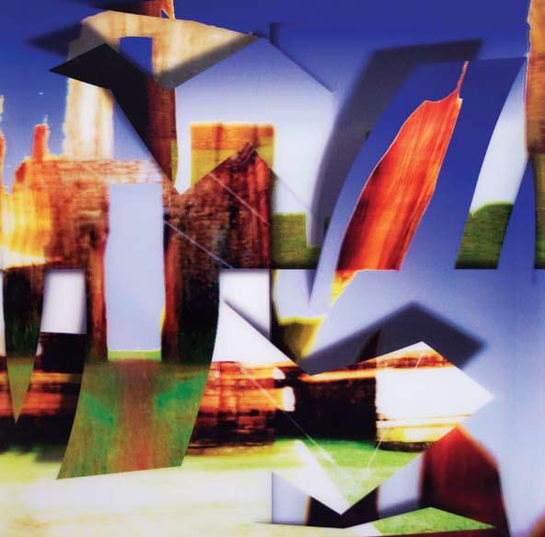

2. We live in a world that disdains admiration. For Descartes, admiration was one of the noblest passions of the soul. I can only imagine how sad this great thinker would be if he knew what had become of his search for indubitable certainties. Paradoxically, clear and distinct knowledge, the corollary of certainty, became blind. Against this, and in the name of a way of thinking that has taken hold in the world and by the world, Merleau-Ponty transformed doubt into perceptive faith. “To reduce perception into the perception of thinking under the pretext that only immanence is sure implies signing an insurance policy against doubt, whose premiums are more onerous than the loss that would be indemnified because it implies the renunciation of the effective world and moving to a type of certainty that never will give us what “there is” in the world.” This notion of perceptive faith comes at just the right moment in this context because what one tries to show is not the order of the demonstration but, rather, the evidence. There is a world and ways of seeing it, whose perception always requires creation. The world is what one sees, together and beyond what is shown, a co-birthing between he who is seeing and what is seen. To paint based upon the experience in the Mission of San Miguel one must accept a starting point and give it a poetic treatment, in order to propel what is seen beyond itself through the seeing-making of the painting. What is of interest is that one does not pass certain places or certain occurrences unscathed. San Miguel certainly is one of them. What in fact happened there? How did such different visions of the world — of the Jesuits and of the Indians — come into common communion with the Christian experience of the sacred? What utopia was that, a type of antecedent for Canudos on the banks of the Uruguay River? Even formulating such questions is difficult for us today. Without a doubt, what remains are the ruins of a still splendorous church pointing towards something mysterious, enchanting the admiring artist with its force. Thus, the experience should not be feared but, rather, taken as an engine or inspiration for a series of paintings. These paintings do not serve to actually illustrate anything. They do not represent San Miguel. What remains of that experience of the sacred, the San Miguel utopia, only can be seen today as a type of (invisible) supplement to these paintings. That is, what exists is Vergara’s painting, with its dense materiality, its agitated coloration, its close spaces, its pulsing texture. There, inside, one glimpses, as something that has no name, the savage and amorous encounter of South American Indians and Jesuit missionaries. This is not shown in the paintings but eventually is revealed in the fright of a disengaged viewing.

3. We have become more proficient in our productive/cognitive capacity, but much less available in our love delivery/power. The Sacred Heart of which Vergara speaks would be a force that puts us on the path toward the other, without subtracting from oneself. Painting only can speak to what it is not speaking of itself, of the pictoric qualities. However, is it possible that every gaze is always disengaged enough to perceive what is not being shown, what is beyond the painting? Availability has to do with the capacity to admire. A somewhat abrupt question: is it that this “de-admiration,” typical of our current suspicious pedagogy, points towards the growing “de-politicizing” in which we are living? A romantic thesis: liberal policy is based on lack of confidence, libertarian policy on the capacity to admire. Let me explain myself: without seeing the other, one does not conceive a world. Painting is extemporary perhaps because it has this affective tonality and this time of admiration. It is political for resisting velocity and imposing upon us an absolute presence, an extended time. One must let time retreat in order to adhere to the transitory nature of appearing. Vergara’s painting is intense and multiple. How could art reveal such a singular occurrence? How to use this admirable encounter with the ruins of a lost world and recreate an affective tonality where lack of trust closed to differences is disarmed? Can art provide what has disappeared and make it new? How to “speak of something” without being illustrative?

4. Vergara’s colors emerge from nature, from the land, from mineral pigments, but contain a sensuality that does not fear the fire of pictoric fantasy. Without the resource of extroverted visuality, the report becomes a one-way street, subtracting the imagination of the act of seeing, confusing creation with reproduction. Reconducting us to this absolutely original moment of encounter and conversion requires a multiplication of visual affections and powers – thus Vergara uses a number of means simultaneously, combining painting, photography, film, monotypes, entwining various ways of feeling. In a short text by Portuguese essayist Eduardo Lourenço about the greatest of all the adventurers who reached the Orient in the 16th Century, Fernão Mendes Pinto, he observes the bedazzlement with the Other, of what had never been previously seen and perceived, which appear in the pages of Peregrinação (Pilgrimage), a report that is at once history and fiction, where fantasy and what is real seem a single thing. At a certain moment, Lourenço writes: “the only thread linking the text to what is real is the entwining or counter-dance of the idealized feelings that announced the geometry of the heart of the Map of Tenderness” . It was this that I liked to observe in Vergara’s paintings, photographs, and monotypes of the Mission of San Miguel: a counter-dance of feelings, a geometry of the heart, a map of tenderness. Returning to what I was speaking of regarding Vergara’s poetic operation, there is in it a need to seek the appropriate means to reveal something that is not known, but rather felt. Change always to reveal the unknown. Allow the multiplicity of voices and affections encounter their own poetic intensity, proper for each situation. The geometry of the heart is what transforms feeling in all ways, typical of the encounter with the Other, through an intense and fearless visuality. The map of tenderness is the opening that is available where the experience of the sacred can gain a vestige of actuality. It is a vestige that appears in the threads stretched by the artist that fill in and inhabit the emptiness in the ruins of the San Miguel Church. In the monotype that carries the heart of stone in the white handkerchief of lost innocence. In the colors, the many colors that we see in these canvasses, with their mineral opacity that opens us up to a profundity, which is nearly delirious, that absorbs the silence of a utopia of conversion. It is a conversion through affection and not by words, and thus derives the relevance of the painting and the tenderness that is resplendent on the surface of the paintings and in the steep passages of light and planes.

Luiz Camillo Osório